Sometimes my high school students ask, “What is evil?” Is it a lack of social conscience or a desire to harm others? Is evil behavior a brain malfunction or mental disorder? Is evil itself an invasion of the devil or a regression to bloodthirsty animalistic survival?

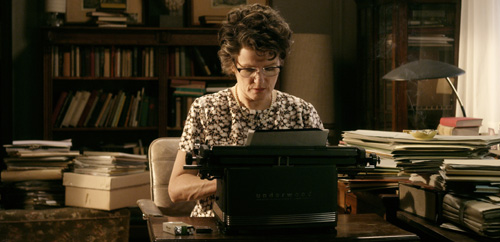

This film on Hannah Arendt, one of the leading political theorists of the 20th century, starts with the apprehension of one of the most famous evil men in world history. Arendt ends up covering his trial for The New Yorker. The problem for her comes not only when she fingers the reason behind the man’s actions but contends the complicity of his victims. The problem for us is taking what we learn from this history and applying it to the current trial of another war criminal and our own personal responsibility.

The film begins on a dark Argentinian night. Our man, coming home from work at a Mercedes-Benz factory outside Buenos Aires, gets off a bus, flips on his flashlight, and begins his walk down a deserted road. We hear the loud night hum of predatory insects, both identifying with this societal miscreant and presaging the capture to come.

Adolf Eichmann, a major instrument in perpetrating the Holocaust, had escaped from earlier US custody and was hunted down by Israeli agents. On a May night in 1960, under an assumed identity, he was shuffling towards home when Israeli agents deftly surrounded him and tossed him into the back of a truck without ceremony. Drugged, he was dressed like a flight attendant and whisked from Argentina on an El Al flight for trial in Israel. About a year later, Hannah Arendt, a reputed professor (Princeton, the University of Chicago, Wesleyan and New School for Social Research in NYC), reports on Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem.

Arendt, a German Jew who had escaped from Nazi internment in 1933, wrote a series of articles on the trial which were published by The New Yorker and then compiled into a book titled Eichmann in Jerusalem.

In her analysis, Arendt notes that there was little evidence to show that Eichmann was acting from sadistic pathology or even virulent anti-Semitism. Instead, noting his repetitive claim that he had been simply following orders, she maintains that his crime was simply not thinking. He thoughtlessly, mindlessly followed through on a horrific path of genocide. She referred to this a “banality of evil” – a void of thought. He failed to think through what he was doing.

“Hannah Arendt” poses more questions than it can possibly answer about evil, responsibility and moral conscience. Arendt’s assertion that Jewish leaders were complicit in the tragedy is not developed. But her observation on Eichmann’s defense, that he was merely following orders, is clear and validated through the infusion of actual trial footage.

If it was wrong for Eichmann to obey Hitler’s insidious orders, wouldn’t it then be right for the rank and file, assuming they were not conditioned to obey orders no matter what, to protest all orders counter to moral conscience? Isn’t that the expectation of a civilized society, particularly in retrospect?

The question remains timely today. This month US Private First Class Bradley Manning is on trial for treason. He exposed US Army policy requiring the liquidation of all people in an area of conflict. After mistakenly killing a Reuters newsman and all innocent humanity around him, US Armed Forces then strafed a good Samaritan and his vehicle with two young children who coincidentally happened upon the scene and attempted to rescue the still-alive Reuters photographer. In disgust at the policy Manning did the only thing he thought was possible to change it – he submitted a top secret videotape of the event to Wikileaks.

If not thinking, not taking a stand against a military order, whether this be during the Holocaust, the My Lai Massacre or in this debacle in Iraq, is punishable, then what protection is there for thinking, for protesting?

To define this kind of evil, following unconscionable orders, as unthinking or banal, opens a door for questions about current affairs, military regulations and our own personal responsibility and moral conscience.

“Hannah Arendt,” one of the most important and well done films of the year, opens in NYC on May 29 and in LA on June 7.

Film Credits

Director: Margarethe von Trotta

Writers: Pam Katz (screenplay), Margarethe von Trotta (screenplay)

Cast: Barbara Sukowa, Axel Milberg, Janet McTeer

Country: Germany, Luxembourg, France

Language: German, French, English, Hebrew, Latin

Release Date: May 29, 2013

Runtime: 113 minutes

Filming Locations: Israel, Luxembourg and Germany

Awards: Four awards, including The German Film Academy recently awarded “Hannah Arendt” its Silver LOLA award for Best Film, and Barbara Sukowa the Best Actress LOLA for her performance.

Website: www.zeitgeistfilms.com/hannaharendt

. . .

Follow Bev Questad on Twitter at http://twitter.com/questad.

And don’t forget to “Like” It’s Just Movies on Facebook at

http://www.facebook.com/itsjustmovies.

Interested in supporting Bradley Manning?

Join Daniel Ellsberg (“I was Bradley Manning): http://www.bradleymanning.org/take-action

Your review and the trailer have sparked my interest. I look forward to seeing the movie, especially because I think we do too little to understand the nature of evil. I hope there are not too many subtitles; my eyes get tired!

I forgot to add that I think Bradley Manning is a hero, NOT a traitor. I hope I can help this courageous and moral young man.

The experience of seeing Eichmann on trial radically changed Arendt’s life. What she saw was a “desk perpetrator”. He himself did not physically murder a single human being, but he was responsible for giving the orders to do so and carrying out the organisational activities that led to the deaths of millions. For Arendt, Eichmann’s deeds were crimes not simply against Jews but “crimes against humanity”. Arendt’s opponents accused her of arrogance and of being soft on Eichmann, but it was more realistic that her very real sense of moral responsibility that led her to try to understand how seemingly normal people like Eichmann could commit crimes of such extraordinary evil.